Genesis 2:15-17; 3:1-7; Matthew 4:1-11

For the past few weeks, we’ve been listening to Jesus preach his first sermon on a hillside. But on this First Sunday in Lent, the lectionary takes us back to the beginning of his ministry.

After his baptism in the Jordan, Matthew tells us that Jesus was led by the Spirit into the wilderness. Not by accident. Not by happenstance. Not by taking a wrong turn. But by the Spirit.

The word Matthew uses suggests Jesus was “launched” into the wilderness, like a ship pushed out into deep water. Because before Jesus could teach God’s reign of love and justice, he had to first confront the seduction of power.

And here’s something we overlook when we read or hear this text. This story is not just about Jesus confronting the seduction of power long ago. But it is about the church, the Body of Christ, confronting that same seduction today.

Every time we come to this table, consuming the Body of Christ, we affirm that we are the Body of Christ. This means the temptations Jesus faces in the wilderness are not his alone. They are ours.

This text in Matthew is about the soul of the church. And it is about the soul of our nation.

Now, before we move too quickly into the temptations, we need to pause and ask: Who is this “devil” in the story? The Greek word is, diabolos, meaning “the accuser,” “the divider,” “the one who slanders and distorts.” In Jewish imagination, this figure is not a rival god equal to God, or the ruler of the underworld, but a voice in the world that tests, twists, and tempts. It’s a force that magnifies fear and manipulates truth. The “devil” is not some scary red creature with horns and pitchfork. It’s the embodiment of every lie seducing humanity to grasp for power and supremacy.

It’s the ancient whisper from Genesis that Eve heard in the garden: “Did God reallysay…?” It’s the voice that promises security through exclusion, glory through domination, and comfort through control. Jesus is not arguing with some cartoon villain in the desert. He’s confronting the deepest distortions of power and faith that still haunt the world.

The tempter doesn’t come when Jesus is strong. The tempter comes when he is depleted, having fasted in the wilderness for forty days, saying “Turn these stones into bread.”

On the surface, it makes perfect sense. It sounds rational, justifiable. You’re starving, physically and spiritually. You need to be fed. So, feed yourself.

But as we are reminded every Sunday when we share Holy Communion together, Jesus understands that bread is much more than calories. Bread is covenant. Bread is relationship. Bread is community around a shared table.

Bread is a holy gift. It’s a process that takes time. There are no shortcuts to baking bread. Bread is not made from stones, but from seed in the ground. From rain and sun. From soil and sweat. From farmers and millers and bakers. From kneading hands and patient waiting.

Plant. Wait. Harvest. Grind. Knead. Bake. Serve. Eat together. Save the seed. Repeat. Shortcutting hunger may satisfy the body in a moment, but it will not nourish the soul, build a community, or strengthen a faith. This is why Jesus answers, “We do not live by bread alone.”

The temptation to turn stones into bread is the temptation to control. But as Master Baker and Christian Educator extraordinaire Maria Niechwiadowicz writes: “The true beauty of bread baking is learning to let go of control, to become attentive to the process instead.” This is why she leads Bake and Pray workshops. She writes: “When we approach baking as liturgy, as a rhythm of prayer, our focus shifts. We begin to notice how the dough has a life of its own, and how God is tending to our own spirits in the same quiet, steady way. Baking bread becomes a practice of noticing. It calls us to slow down, pay attention, and rest.”

And this where this temptation becomes political today.

Religious nationalism promises quick fixes and easy solutions to our fears. It says we can solve our complex problems with control, force, and exclusion. It offers the stone-bread of hatred—hard, fast, satisfying in the mouth for a moment, but incapable of sustaining life.

Because cannot build a peaceful and just world with stone-bread. A nation’s soul cannot nourished with anger. The problem of human hunger, physical or spiritual, cannot be solved by shortcutting the slow, relational, justice-centered work that real, holy, God-bread requires.

Our broken nation cannot heal by consuming stone-bread of fear. But we can heal with the God-bread of empathy, repair and reconciliation.

The beloved community cannot be created with the stone-bread of alienation, separation, or domination. But it can and it will with the God-bread of acceptance, equity, and inclusion.

Lent is not a season for quick fixes. It’s a season for planting. It’s a holy time to ask: How are we satisfying our hunger? How are we healing the world? How are we making our bread? Are we grasping at stones because they are quick and easy to throw? Or are we willing to do the slow, sometimes exhausting, long work that nurtures body and soul: the work of planting justice, kneading mercy, baking reconciliation, and setting a table wide enough for all of God’s children?[i]

It is then the tempter takes Jesus to the pinnacle of the temple, to the architecture of faith, the center of religious life. And there, you could say, “in church,” the devil quotes scripture. That’s right, the devil is in the church and the devil has memorized some Bible verses! “Throw yourself down. God will catch you. The angels will bear you up.”

On the surface, it sounds faithful. It even sounds biblical. But this temptation is about performing faith instead of living it. It’s hanging the ten commandments on a wall of classrooms, or mandating Bible teaching in the classrooms, while refusing to fund the classrooms, to feed the children, and to pay the teachers a living wage. It’s a mouth full of scripture and a heart full of hate. It’s about manufacturing a religious spectacle to prove to others that you are on the side of God.

And Jesus refuses: “Do not put the Lord your God to the test.”

In other words: Authentic faith does not need a stunt. Later, Jesus will say, if you want people to know you are on the side of God, that you are my disciples, love one another as you have seen me love you.

Jesus understands that faith, like bread, takes time, patience, and love—in quiet obedience, in daily prayer, in healing the sick one body at a time, in touching the untouchable, in eating with sinners, in welcoming children, in doing the difficult work of liberation and reconciliation, in walking dusty, lonesome roads to meet people wherever they are.

You don’t build faith in God by jumping off buildings. You build it by walking steadily in love, loving your neighbors as you love yourselves, standing up for and with, the least of these.

Religious nationalism thrives on religious stunts and theatrics. It believes that if we can just show strength (visible, loud, triumphant) then that must mean God is with us.

But Jesus understands when faith becomes performance, it stops being faith. And when the church becomes obsessed with visibility and influence, it forgets the slow, steady work of justice.

The kin-dom of God grows more like yeast than fireworks. It’s quiet, persistent, transformative from the inside out. The season of Lent invites us to step down from the pinnacle to practice the long obedience of mercy, truth-telling, and solidarity. No stunts. No spectacles. Just faithfulness.

Finally, the tempter says the quiet part out loud. No more talking about hunger. No more scripture games. Just a mountain. A wide view. And a deal.

“All the kingdoms of the world and all their splendor I will give you, if you will fall down and worship me.” There it is. The devil just comes out and says it with breathtaking honesty. Worship power, and you can have power. Bow down, bend the knee, and you can rule.

No shortcuts disguised as feeding oneself. No spectacle disguised as faith. Just the ancient bargain from the Garden of Eden spoken out loud: “You can be like God.” You can take control, secure dominance, and make it all yours.

And here’s what makes this temptation so dangerous: it would have worked.

Jesus could have enforced God’s reign of love and justice from the top down. He could have imposed righteousness. He could have seized the machinery of empire and steered it toward good. But that’s not the kingdom of God. Because the moment you bow to power to get power, power becomes your god.

Thus, Jesus refuses to negotiate. “Away with you, Satan, you tempter and deceiver! For it is written: Worship the Lord your God, and serve God only.” Jesus refuses to confuse the reign of God with the rule of empire.

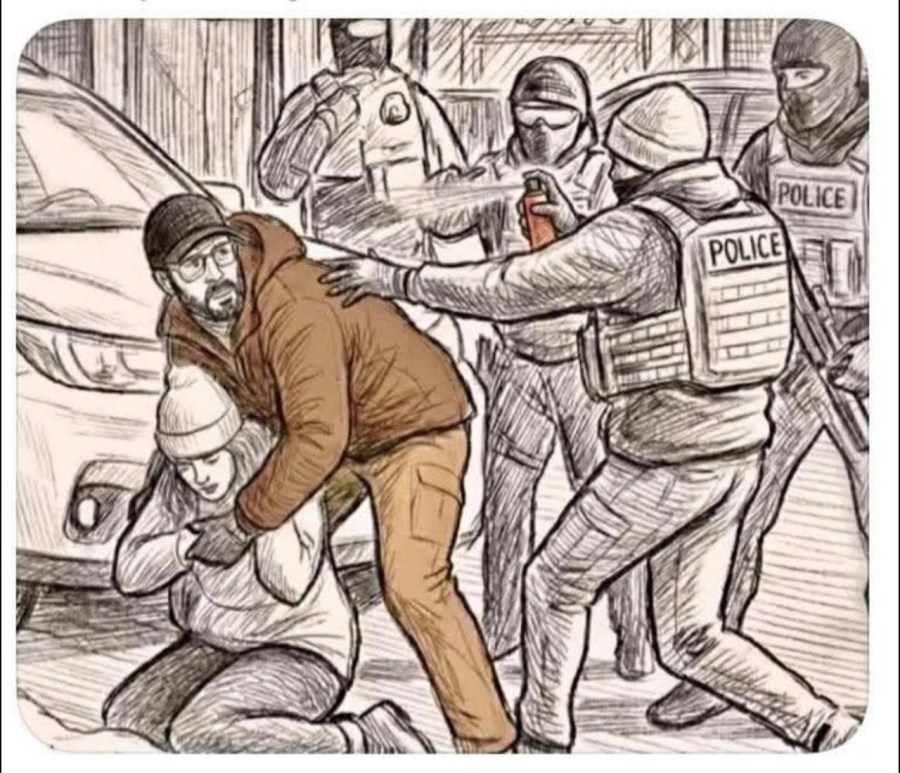

Religious nationalism makes this exact offer to the church. It says: “Align yourself with political control.” “Trade your prophetic voice for proximity to the throne.” “Overlook hate and greed, even sexual assault and pedophilia, if you can getyour way.” “Secure cultural dominance, and then you can shape the future.”

But we cannot build beloved community by bowing to power or create justice by surrendering to supremacy.

We cannot proclaim good news to the poor and liberation to the oppressed while kneeling before systems that require the poor to remain poor and the oppressed to remain bound.

The kingdom of God does not arrive through coercion but grows the way bread grows: through seed in soil; through slow, tedious, patient work; through trust; through shared tables and a cross-shaped love.

This path looks weak from the mountaintop. It doesn’t glitter. It doesn’t dominate. It doesn’t trend or immediately go viral. And it leads, eventually, to another hill, not a throne, but a cross.

And that is the decisive rejection of this temptation.

Jesus ultimately chooses suffering love over controlling power. He chooses grace over domination. He chooses faithfulness over force, nonviolence over violence. And because he does, angels come to him in the wilderness and minister to him.

Not because he won. But because he refused to bow.

Lent asks the church the same question the wilderness asked Jesus:

Whom will you worship?

Will we bow to the splendor of control?

Will we trade love of neighbor for political power?

Will we accept injustice if it keeps “our side” in charge?

Or will we worship the Lord our God, and serve God only?

This Lent, may we refuse to bow and resist the bargain. And choose the slow, holy work of love, mercy, and justice.

May we plant gardens instead of building empires.

May we always choose to worship God alone.

Amen.